Richard Rasa – Sitar

Marlis Jermutus – Tamboura

Bastian Jermutus – Synthesizers

Listen to a short sample from the CD Lakshmi Smiles

“Ware Soku Kami Nari”

Three musicians perform in meditative trance, egos suspended, musical direction determined by the energy of the moment and the flight plan of the Starseed. A suggestion for listening to Starseed music . . . find a comfortable space and moment. Turn the volume up loud to become fully exposed to the entire range of musical overtones. Close your eyes and relax. Prepare for a voyage. Rather than the formulated verses and chorus’ of popular music, this music follows a form more akin to storytelling.

About vibrations… play any musical note and nature responds by sounding a corresponding series of notes that mathematically build themselves up from the vibration of the first note. Usually we don’t hear these overtones or harmonics because they are normally very soft, and the music usually moves so fast that the overtones haven’t time to ring out. If we carefully listen to the overtones we hear an exquisite series of notes uniformly ordered in a precise relationship.

About vibrations… play any musical note and nature responds by sounding a corresponding series of notes that mathematically build themselves up from the vibration of the first note. Usually we don’t hear these overtones or harmonics because they are normally very soft, and the music usually moves so fast that the overtones haven’t time to ring out. If we carefully listen to the overtones we hear an exquisite series of notes uniformly ordered in a precise relationship.

The natural overtones made more audible by the design of Indian instruments are used to stimulate a sympathetic vibration in the listener, a vibration that Indian philosophers believe connects the human vibrational frequency to the waves of the natural overtone series, which vibrate through all levels of physical reality.  This idea follows the belief that the 49 sounds in the Sanskrit language were “discovered” by yogis who heard these sounds after years of meditating on 49 parts of the human body’s glandular structure. Thus it is said that Sanskrit, and its ritual usage, developed as a way of massaging the body into a state of heightened functionality. Indian instruments were designed to mimic the human voice and the corresponding vibrational patterns that ensue when the voice box vibrates and the environment responds.

This idea follows the belief that the 49 sounds in the Sanskrit language were “discovered” by yogis who heard these sounds after years of meditating on 49 parts of the human body’s glandular structure. Thus it is said that Sanskrit, and its ritual usage, developed as a way of massaging the body into a state of heightened functionality. Indian instruments were designed to mimic the human voice and the corresponding vibrational patterns that ensue when the voice box vibrates and the environment responds.

Starseed interlaces this vibrational matrix with a mental intention focused on healing and peace. They play amazingly vibrational instruments while in a meditative state guided by an auto-suggested healing meme. The meme is implanted and reinforced by a rigorous attention to set and setting. The music studio is their temple. They begin each session with meditation.

Most of Starseed’s pieces are stream of consciousness events where only the chosen musical mode defines the content of the musical phrases, and even then, an occasional “outlaw” note will be invited into a phrase simply because nature refuses to be normal, and when the ordered brain of the musician yields to a  state of free improvisation, chaos appears to be nature’s insistent playmate. A few of their pieces lovingly, with numinous intoxication, play with bits of melodic structure borrowed from traditional sources. For example, The Vibrant Formula on The Temple of Me improvises a version of the Gayatri Mantra, a Sanskrit prayer for peace and higher intelligence. The Serpent’s Explanation, on the same CD, borrows the theme of the traditional Indian raga Yeman. Opening the DNA Curtain on Live in Mt Shasta recreates an Amazonian shaman’s icaro, a ritual healing melody.

state of free improvisation, chaos appears to be nature’s insistent playmate. A few of their pieces lovingly, with numinous intoxication, play with bits of melodic structure borrowed from traditional sources. For example, The Vibrant Formula on The Temple of Me improvises a version of the Gayatri Mantra, a Sanskrit prayer for peace and higher intelligence. The Serpent’s Explanation, on the same CD, borrows the theme of the traditional Indian raga Yeman. Opening the DNA Curtain on Live in Mt Shasta recreates an Amazonian shaman’s icaro, a ritual healing melody.

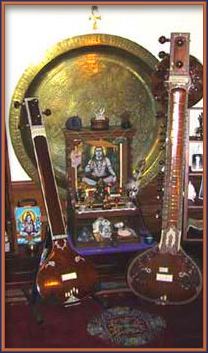

The sitar has four main strings on which the melody is played. The instrument’s sixteen other strings are struck for harmonic drone effects, or they simply sound unstruck as they respond sympathetically to the other strings. The tanboura has five strings tuned only to the first and fifth notes of the scale. This repetition of the two most dominant notes of a scale reinforces the ground upon which the overtone series is built.

The synthesizer in Starseed’s music also reinforces the first and fifth notes of the scale, but adds the vast diversity of electronic tonality, creating an atmosphere rich in harmonic nutrients. Bastian’s synthesizer provides the landscape. Marlis’ tamboura pulsates with a muse’s whimsical breathing of the overtones. Rasa’s sitar describes a melodic journey that, sometimes dancing out of standard rhythms, sometimes cavorting with “forbidden” notes, travels in a storyline as familiar but unpredictable as a human life.

Create your own set and setting for this music

and the overtones will massage you.

Close your eyes, breathe calmly, relax and listen deeply.

Rasa alternates between two sitars, one made in 1970, the other in 2000. The 1970 sitar was made by legendary instrument maker Hiren Roy of Calcutta. The 2000 sitar was made by Hiren Roy’s son.

Marlis plays a 1999 Hiren Roy instrumental tamboura.

Bastian plays a Korg Wave Station, a Kurzweil 2000, a Korg Trinity, and a Waldorf Microwave XT.

A word about modes . . .

We are curious to identify and understand the musical modes chosen in our music. A mode is the (usually) seven notes chosen from the twelve notes of the octave that form the scale used in a musical piece.  Each mode has its own distinct personality. We often play in the Lesbian mode. Normal musicologists refer to it as the Mixolydian Mode, but the scale comes from the island and people of Lesbos, and since the seven Western modes come from Greek tribes, and there was never a Mixolydian tribe, I prefer to follow musicologist Kay Gardner and call the mode Lesbian. The Lesbian mode usually brings out a light joy in listeners. Marlis believes it to be one of the most healing of all the modes. The friendly and emotional Dorian mode is one of Bastian’s favorites. When I tune to the Dorian, I often end up playing phrases suggestive of bittersweet Blues. The Dorian and Ionian modes form the basis for a lot of familiar Western pop music. I love all the modes and don’t have a favorite, but because our Western ears feel in such ease with the Lesbian, Dorian, and Ionian modes, we play them often. I value those moments, however, when we tune away from these standards, bringing us into intriguing less familiar modes. The first raga I learned in India was Rag Yeman, which is tuned to what we call the Lydian Mode. Because of its raised fourth tone, an uncommon tension (for Western ears) is created between the fourth and fifth tones. This is the same mathematical relationship the seventh and the tonic (first) note of the scale share, so even though Lydian’s strange Eastern sound seems unusual to Western ears, I find that fourth/fifth and seventh/tonic relationship balances the seven notes of the scale in a way that seems unusually playful. In The Republic, Plato suggested banning the Lydian mode because he found it too “feminine.” I think that says more about ancient perspectives, than the quality of the mode.

Each mode has its own distinct personality. We often play in the Lesbian mode. Normal musicologists refer to it as the Mixolydian Mode, but the scale comes from the island and people of Lesbos, and since the seven Western modes come from Greek tribes, and there was never a Mixolydian tribe, I prefer to follow musicologist Kay Gardner and call the mode Lesbian. The Lesbian mode usually brings out a light joy in listeners. Marlis believes it to be one of the most healing of all the modes. The friendly and emotional Dorian mode is one of Bastian’s favorites. When I tune to the Dorian, I often end up playing phrases suggestive of bittersweet Blues. The Dorian and Ionian modes form the basis for a lot of familiar Western pop music. I love all the modes and don’t have a favorite, but because our Western ears feel in such ease with the Lesbian, Dorian, and Ionian modes, we play them often. I value those moments, however, when we tune away from these standards, bringing us into intriguing less familiar modes. The first raga I learned in India was Rag Yeman, which is tuned to what we call the Lydian Mode. Because of its raised fourth tone, an uncommon tension (for Western ears) is created between the fourth and fifth tones. This is the same mathematical relationship the seventh and the tonic (first) note of the scale share, so even though Lydian’s strange Eastern sound seems unusual to Western ears, I find that fourth/fifth and seventh/tonic relationship balances the seven notes of the scale in a way that seems unusually playful. In The Republic, Plato suggested banning the Lydian mode because he found it too “feminine.” I think that says more about ancient perspectives, than the quality of the mode.

As a science of the senses, music can heal the heart and body.

– Richard Rasa

“This music – intricate yet melodic as Bach,

austere as a Zen shrine, sensory as a massage

– seems like aural eroticism to me.”

– Robert Anton Wilson

“Contemporary Raga”

– Patrick Bernard

“Innerspace Music”

– Peter Ziegelmeier (Kode IV)

“You Rock!”

– Shannon Burke, The Village Oracle

“I just fell into the most relaxing calm, allowing myself to imagine exotic birds flitting through Bastian’s soundboard, to explore different altitudes with Rasa’s beautiful sitar, to feel safe and balanced with Marlis’ rhythms. I loved every minute of the music.”

– Kim Presley, Director of Liberty Arts Gallery

“Delicate yet powerful sonic tapestry”

– Todd Friedlander, abstract artist

“Nothing is unbalanced. Bastian coaxes from his synthesizers breathtaking shivers, and captures sublime moods of awe and reverence beautifully. Ma’s tanboura, the most subtle of the instruments, is so uniquely her that it is uncanny. A breeze, a playful muse, and a pulse (though more like the waves of the wind, or the breath, or the tides, than any kind of drum) at once, it sends continuous waves of ecstasy through the music. Rasa has a way of making his sympathetic strings literally sing that is unlike that of any sitarist I’m familiar with. Part of this is his insistence on utterly meticulous tuning, and part of it is his willingness to give the instrument its chance to speak, rather than simply imposing his thoughts on it. It is astounding how long his sympathetics will continue to ring out for; how rich the overtones he finds simply by letting the instrument speak. In his hands, this preternaturally responsive instrument will bring you into spaces you had no idea existed.”

– from Brian Em’s review of Entering the Ambient Temple